General Full Factorial Designs

Experiments with two or more factors are encountered frequently. The best way to carry out such experiments is by using factorial experiments. Factorial experiments are experiments in which all combinations of factors are investigated in each replicate of the experiment. Factorial experiments are the only means to completely and systematically study interactions between factors in addition to identifying significant factors. One-factor-at-a-time experiments (where each factor is investigated separately by keeping all the remaining factors constant) do not reveal the interaction effects between the factors. Further, in one-factor-at-a-time experiments full randomization is not possible.

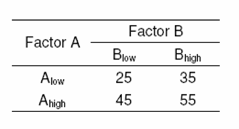

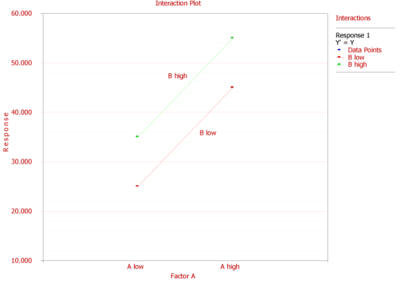

To illustrate factorial experiments consider an experiment where the response is investigated for two factors, [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]. Assume that the response is studied at two levels of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ {{A}_{\text{low}}}\,\! }[/math] representing the lower level of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{A}_{\text{high}}}\,\! }[/math] representing the higher level of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math]. Similarly, let [math]\displaystyle{ {{B}_{\text{low}}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{B}_{\text{high}}}\,\! }[/math] represent the two levels of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] that are being investigated in this experiment. Since there are two factors with two levels, a total of [math]\displaystyle{ 2\times 2=4\,\! }[/math] combinations exist ([math]\displaystyle{ {{A}_{\text{low}}}\,\! }[/math] - [math]\displaystyle{ {{B}_{\text{low}}}\,\! }[/math], - [math]\displaystyle{ {{B}_{\text{high}}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{A}_{\text{high}}}\,\! }[/math] - [math]\displaystyle{ {{B}_{\text{low}}}\,\! }[/math], - [math]\displaystyle{ {{B}_{\text{high}}}\,\! }[/math]). Thus, four runs are required for each replicate if a factorial experiment is to be carried out in this case. Assume that the response values for each of these four possible combinations are obtained as shown in the third table.

Investigating Factor Effects

The effect of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] on the response can be obtained by taking the difference between the average response when [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is high and the average response when [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is low. The change in the response due to a change in the level of a factor is called the main effect of the factor. The main effect of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] as per the response values in the third table is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} A= & Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{A}_{\text{high}}}-Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{A}_{\text{low}}} \\ = & \frac{45+55}{2}-\frac{25+35}{2} \\ = & 50-30 \\ = & 20 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, when [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is changed from the lower level to the higher level, the response increases by 20 units. A plot of the response for the two levels of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] at different levels of [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] is shown in the figure above. The plot shows that change in the level of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] leads to an increase in the response by 20 units regardless of the level of [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]. Therefore, no interaction exists in this case as indicated by the parallel lines on the plot. The main effect of [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] can be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} B= & Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{B}_{\text{high}}}-Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{B}_{\text{low}}} \\ = & \frac{35+55}{2}-\frac{25+45}{2} \\ = & 45-35 \\ = & 10 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Investigating Interactions

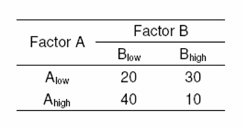

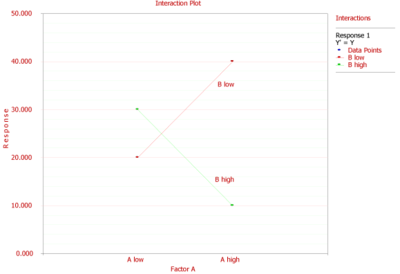

Now assume that the response values for each of the four treatment combinations were obtained as shown in the fourth table. The main effect of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] in this case is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} A= & Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{A}_{\text{high}}}-Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{A}_{\text{low}}} \\ = & \frac{40+10}{2}-\frac{20+30}{2} \\ = & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

It appears that [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] does not have an effect on the response. However, a plot of the response of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] at different levels of [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] shows that the response does change with the levels of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] but the effect of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] on the response is dependent on the level of [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] (see the figure below). Therefore, an interaction between [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] exists in this case (as indicated by the non-parallel lines of the figure). The interaction effect between [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] can be calculated as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} AB= & Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{A}_{\text{high}}}\text{-}{{B}_{\text{high}}}\text{ }and\text{ }{{A}_{\text{low}}}\text{-}{{B}_{\text{low}}}- \\ & Average\text{ }response\text{ }at\text{ }{{A}_{\text{low}}}\text{-}{{B}_{\text{high}}}\text{ }and\text{ }{{A}_{\text{high}}}\text{-}{{B}_{\text{low}}} \\ = & \frac{10+20}{2}-\frac{40+30}{2} \\ = & -20 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Note that in this case, if a one-factor-at-a-time experiment were used to investigate the effect of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] on the response, it would lead to incorrect conclusions. For example, if the response at factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] was studied by holding [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] constant at its lower level, then the main effect of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] would be obtained as [math]\displaystyle{ 40-20=20\,\! }[/math], indicating that the response increases by 20 units when the level of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is changed from low to high. On the other hand, if the response at factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] was studied by holding [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] constant at its higher level than the main effect of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] would be obtained as [math]\displaystyle{ 10-30=-20\,\! }[/math], indicating that the response decreases by 20 units when the level of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is changed from low to high.

Analysis of General Factorial Experiments

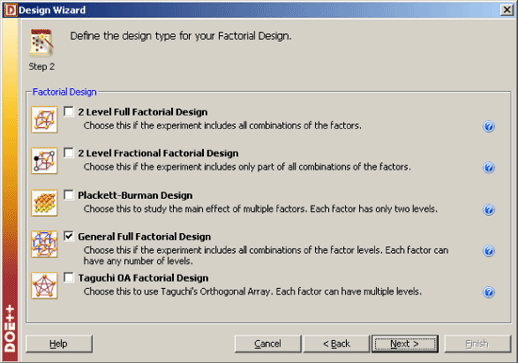

In DOE++, factorial experiments are referred to as factorial designs. The experiments explained in this section are referred to as general factorial designs. This is done to distinguish these experiments from the other factorial designs supported by DOE++ (see the figure below).

The other designs (such as the two level full factorial designs that are explained in Two Level Factorial Experiments) are special cases of these experiments in which factors are limited to a specified number of levels. The ANOVA model for the analysis of factorial experiments is formulated as shown next. Assume a factorial experiment in which the effect of two factors, [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math], on the response is being investigated. Let there be [math]\displaystyle{ {{n}_{a}}\,\! }[/math] levels of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{n}_{b}}\,\! }[/math] levels of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]. The ANOVA model for this experiment can be stated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{ijk}}=\mu +{{\tau }_{i}}+{{\delta }_{j}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}+{{\epsilon }_{ijk}}\,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \,\! }[/math] represents the overall mean effect

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] is the effect of the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ i=1,2,...,{{n}_{a}}\,\! }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] is the effect of the [math]\displaystyle{ j\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ j=1,2,...,{{n}_{b}}\,\! }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\,\! }[/math] represents the interaction effect between [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\epsilon }_{ijk}}\,\! }[/math] represents the random error terms (which are assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero and variance of [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }^{2}}\,\! }[/math])

- and the subscript [math]\displaystyle{ k\,\! }[/math] denotes the [math]\displaystyle{ m\,\! }[/math] replicates ([math]\displaystyle{ k=1,2,...,m\,\! }[/math])

Since the effects [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{i}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\,\! }[/math] represent deviations from the overall mean, the following constraints exist:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\tau }_{i}}=0\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\delta }_{j}}=0\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}=0\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}=0\,\! }[/math]

Hypothesis Tests in General Factorial Experiments

These tests are used to check whether each of the factors investigated in the experiment is significant or not. For the previous example, with two factors, [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math], and their interaction, [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math], the statements for the hypothesis tests can be formulated as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \begin{matrix} 1. & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{0}}:{{\tau }_{1}}={{\tau }_{2}}=...={{\tau }_{{{n}_{a}}}}=0\text{ (Main effect of }A\text{ is absent)} \\ & \begin{matrix} {} & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{1}}:{{\tau }_{i}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }i \\ & \begin{matrix} 2. & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{0}}:{{\delta }_{1}}={{\delta }_{2}}=...={{\delta }_{{{n}_{b}}}}=0\text{ (Main effect of }B\text{ is absent)} \\ & \begin{matrix} {} & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{1}}:{{\delta }_{j}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }j \\ & \begin{matrix} 3. & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{0}}:{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}={{(\tau \delta )}_{12}}=...={{(\tau \delta )}_{{{n}_{a}}{{n}_{b}}}}=0\text{ (Interaction }AB\text{ is absent)} \\ & \begin{matrix} {} & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{1}}:{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }ij \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The test statistics for the three tests are as follows:

- 1)[math]\displaystyle{ {(F_{0})}_{A} = \frac{MS_{A}}{MS_{E}}\,\! }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ MS_{A}\,\! }[/math] is the mean square due to factor [math]\displaystyle{ {A}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {MS_E}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square.

- 1)[math]\displaystyle{ {(F_{0})}_{A} = \frac{MS_{A}}{MS_{E}}\,\! }[/math]

- 2)[math]\displaystyle{ {(F_{0})_{B}} = \frac{MS_B}{MS_E}\,\! }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ MS_{B}\,\! }[/math] is the mean square due to factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ MS_{E}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square.

- 2)[math]\displaystyle{ {(F_{0})_{B}} = \frac{MS_B}{MS_E}\,\! }[/math]

- 3)[math]\displaystyle{ {(F_{0})_{AB}} = \frac{MS_{AB}}{MS_{E}}\,\! }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ MS_{AB}\,\! }[/math] is the mean square due to interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ MS_{E}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square.

- 3)[math]\displaystyle{ {(F_{0})_{AB}} = \frac{MS_{AB}}{MS_{E}}\,\! }[/math]

The tests are identical to the partial [math]\displaystyle{ F\,\! }[/math] test explained in Multiple Linear Regression Analysis. The sum of squares for these tests (to obtain the mean squares) are calculated by splitting the model sum of squares into the extra sum of squares due to each factor. The extra sum of squares calculated for each of the factors may either be partial or sequential. For the present example, if the extra sum of squares used is sequential, then the model sum of squares can be written as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{TR}}=S{{S}_{A}}+S{{S}_{B}}+S{{S}_{AB}}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{TR}}\,\! }[/math] represents the model sum of squares, [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{A}}\,\! }[/math] represents the sequential sum of squares due to factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{B}}\,\! }[/math] represents the sequential sum of squares due to factor and [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{AB}}\,\! }[/math] represents the sequential sum of squares due to the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math].

The mean squares are obtained by dividing the sum of squares by the associated degrees of freedom. Once the mean squares are known the test statistics can be calculated. For example, the test statistic to test the significance of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] (or the hypothesis [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\tau }_{i}}=0\,\! }[/math]) can then be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{({{F}_{0}})}_{A}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{A}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{S{{S}_{A}}/dof(S{{S}_{A}})}{S{{S}_{E}}/dof(S{{S}_{E}})} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Similarly the test statistic to test significance of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] and the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] can be respectively obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{({{F}_{0}})}_{B}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{B}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{S{{S}_{B}}/dof(S{{S}_{B}})}{S{{S}_{E}}/dof(S{{S}_{E}})} \\ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{AB}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{AB}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{S{{S}_{AB}}/dof(S{{S}_{AB}})}{S{{S}_{E}}/dof(S{{S}_{E}})} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

It is recommended to conduct the test for interactions before conducting the test for the main effects. This is because, if an interaction is present, then the main effect of the factor depends on the level of the other factors and looking at the main effect is of little value. However, if the interaction is absent then the main effects become important.

Example

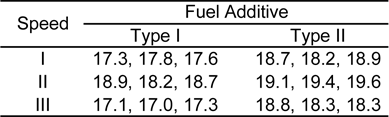

Consider an experiment to investigate the effect of speed and type of fuel additive used on the mileage of a sports utility vehicle. Three speeds and two types of fuel additives are investigated. Each of the treatment combinations are replicated three times. The mileage values observed are displayed in the fifth table.

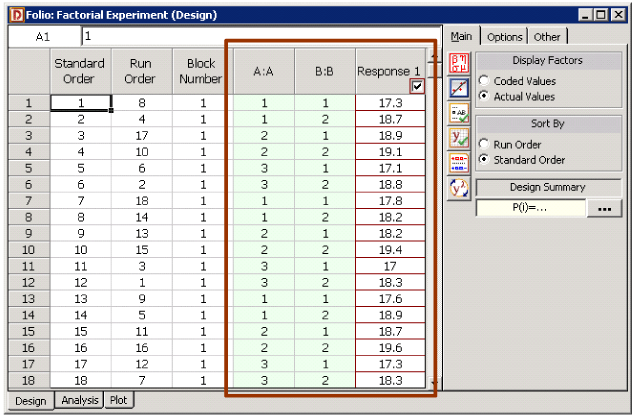

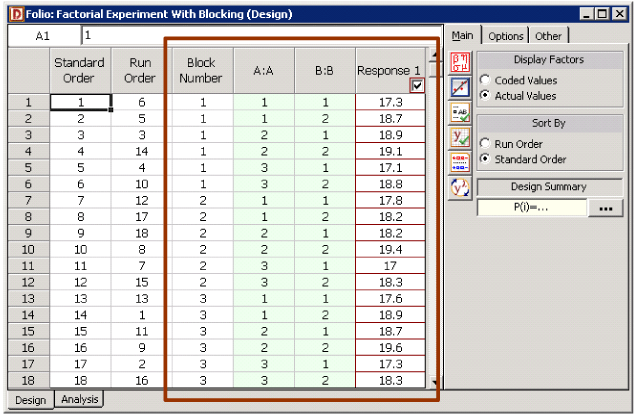

The experimental design for the data in the fifth table is shown in the figure below. In the figure, the factor Speed is represented as factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and the factor Fuel Additive is represented as factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]. The experimenter would like to investigate if speed, fuel additive or the interaction between speed and fuel additive affects the mileage of the sports utility vehicle. In other words, the following hypotheses need to be tested:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \begin{matrix} 1. & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{0}}:{{\tau }_{1}}={{\tau }_{2}}={{\tau }_{3}}=0\text{ (No main effect of factor }A\text{, speed)} \\ & \begin{matrix} {} & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{1}}:{{\tau }_{i}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }i \\ & \begin{matrix} 2. & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{0}}:{{\delta }_{1}}={{\delta }_{2}}={{\delta }_{3}}=0\text{ (No main effect of factor }B\text{, fuel additive)} \\ & \begin{matrix} {} & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{1}}:{{\delta }_{j}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }j \\ & \begin{matrix} 3. & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{0}}:{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}={{(\tau \delta )}_{12}}=...={{(\tau \delta )}_{33}}=0\text{ (No interaction }AB\text{)} \\ & \begin{matrix} {} & {} \\ \end{matrix}{{H}_{1}}:{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }ij \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The test statistics for the three tests are:

- 1.[math]\displaystyle{ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{A}}=\frac{M{{S}_{A}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{A}}\,\! }[/math] is the mean square for factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{E}}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square

- 1.[math]\displaystyle{ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{A}}=\frac{M{{S}_{A}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

- 2.[math]\displaystyle{ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{B}}=\frac{M{{S}_{B}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{B}}\,\! }[/math] is the mean square for factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{E}}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square

- 2.[math]\displaystyle{ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{B}}=\frac{M{{S}_{B}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

- 3.[math]\displaystyle{ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{AB}}=\frac{M{{S}_{AB}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{AB}}\,\! }[/math] is the mean square for interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{E}}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square

- 3.[math]\displaystyle{ {{({{F}_{0}})}_{AB}}=\frac{M{{S}_{AB}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

The ANOVA model for this experiment can be written as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{ijk}}=\mu +{{\tau }_{i}}+{{\delta }_{j}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}+{{\epsilon }_{ijk}}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] represents the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th treatment of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] (speed) with [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math] =1, 2, 3; [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] represents the [math]\displaystyle{ j\,\! }[/math]th treatment of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] (fuel additive) with [math]\displaystyle{ j\,\! }[/math] =1, 2; and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\,\! }[/math] represents the interaction effect. In order to calculate the test statistics, it is convenient to express the ANOVA model of the equation given above in the form [math]\displaystyle{ y=X\beta +\epsilon \,\! }[/math]. This can be done as explained next.

Expression of the ANOVA Model as [math]\displaystyle{ y=X\beta +\epsilon \,\! }[/math]

Since the effects [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{i}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\,\! }[/math] represent deviations from the overall mean, the following constraints exist. Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \underset{i=1}{\overset{3}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\tau }_{i}}= & 0 \\ \text{or }{{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}}+{{\tau }_{3}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, only two of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] effects are independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math] are independent, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{3}}=-({{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}})\,\! }[/math]. (The null hypothesis to test the significance of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] can be rewritten using only the independent effects as [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\tau }_{1}}={{\tau }_{2}}=0\,\! }[/math].) DOE++ displays only the independent effects because only these effects are important to the analysis. The independent effects, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], are displayed as A[1] and A[2] respectively because these are the effects associated with factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] (speed).

Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \underset{j=1}{\overset{2}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\delta }_{j}}= & 0 \\ \text{or }{{\delta }_{1}}+{{\delta }_{2}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, only one of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] effects are independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] is independent, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{2}}=-{{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math]. (The null hypothesis to test the significance of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] can be rewritten using only the independent effect as [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\delta }_{1}}=0\,\! }[/math].) The independent effect [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] is displayed as B:B in DOE++.

Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \underset{i=1}{\overset{3}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}= & 0 \\ \text{and }\underset{j=1}{\overset{2}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}= & 0 \\ \text{or }{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{31}}= & 0 \\ {{(\tau \delta )}_{12}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{22}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{32}}= & 0 \\ \text{and }{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{12}}= & 0 \\ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{22}}= & 0 \\ {{(\tau \delta )}_{31}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{32}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The last five equations given above represent four constraints, as only four of these five equations are independent. Therefore, only two out of the six [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}\,\! }[/math] effects are independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math] are independent, the other four effects can be expressed in terms of these effects. (The null hypothesis to test the significance of interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] can be rewritten using only the independent effects as [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}={{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}=0\,\! }[/math].) The effects [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math] are displayed as A[1]B and A[2]B respectively in DOE++.

The regression version of the ANOVA model can be obtained using indicator variables, similar to the case of the single factor experiment in Fitting ANOVA Models. Since factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] has three levels, two indicator variables, [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{2}}\,\! }[/math], are required which need to be coded as shown next:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \text{Treatment Effect }{{\tau }_{1}}: & {{x}_{1}}=1,\text{ }{{x}_{2}}=0 \\ \text{Treatment Effect }{{\tau }_{2}}: & {{x}_{1}}=0,\text{ }{{x}_{2}}=1\text{ } \\ \text{Treatment Effect }{{\tau }_{3}}: & {{x}_{1}}=-1,\text{ }{{x}_{2}}=-1\text{ } \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] has two levels and can be represented using one indicator variable, [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{3}}\,\! }[/math], as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \text{Treatment Effect }{{\delta }_{1}}: & {{x}_{3}}=1 \\ \text{Treatment Effect }{{\delta }_{2}}: & {{x}_{3}}=-1 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] interaction will be represented by all possible terms resulting from the product of the indicator variables representing factors [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]. There are two such terms here - [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{1}}{{x}_{3}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{2}}{{x}_{3}}\,\! }[/math]. The regression version of the ANOVA model can finally be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ Y=\mu +{{\tau }_{1}}\cdot {{x}_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}}\cdot {{x}_{2}}+{{\delta }_{1}}\cdot {{x}_{3}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\cdot {{x}_{1}}{{x}_{3}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\cdot {{x}_{2}}{{x}_{3}}+\epsilon \,\! }[/math]

In matrix notation this model can be expressed as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ y=X\beta +\epsilon \,\! }[/math]

- where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ y=\left[ \begin{matrix} {{Y}_{111}} \\ {{Y}_{211}} \\ {{Y}_{311}} \\ {{Y}_{121}} \\ {{Y}_{221}} \\ {{Y}_{321}} \\ {{Y}_{112}} \\ {{Y}_{212}} \\ . \\ . \\ {{Y}_{323}} \\ \end{matrix} \right]=X\beta +\epsilon =\left[ \begin{matrix} 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & -1 & -1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & -1 & -1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & -1 & 0 & -1 \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ . & . & . & . & . & . \\ . & . & . & . & . & . \\ 1 & -1 & -1 & -1 & 1 & 1 \\ \end{matrix} \right]\left[ \begin{matrix} \mu \\ {{\tau }_{1}} \\ {{\tau }_{2}} \\ {{\delta }_{1}} \\ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}} \\ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}} \\ \end{matrix} \right]+\left[ \begin{matrix} {{\epsilon }_{111}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{211}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{311}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{121}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{221}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{321}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{112}} \\ {{\epsilon }_{212}} \\ . \\ . \\ {{\epsilon }_{323}} \\ \end{matrix} \right]\,\! }[/math]

The vector [math]\displaystyle{ y\,\! }[/math] can be substituted with the response values from the fifth table to get:

- [math]\displaystyle{ y=\left[ \begin{matrix} {{Y}_{111}} \\ {{Y}_{211}} \\ {{Y}_{311}} \\ {{Y}_{121}} \\ {{Y}_{221}} \\ {{Y}_{321}} \\ {{Y}_{112}} \\ {{Y}_{212}} \\ . \\ . \\ {{Y}_{323}} \\ \end{matrix} \right]=\left[ \begin{matrix} 17.3 \\ 18.9 \\ 17.1 \\ 18.7 \\ 19.1 \\ 18.8 \\ 17.8 \\ 18.2 \\ . \\ . \\ 18.3 \\ \end{matrix} \right]\,\! }[/math]

Knowing [math]\displaystyle{ y\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ X\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \,\! }[/math], the sum of squares for the ANOVA model and the extra sum of squares for each of the factors can be calculated. These are used to calculate the mean squares that are used to obtain the test statistics.

Calculation of Sum of Squares for the Model

The model sum of squares, [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{TR}}\,\! }[/math], for the regression version of the ANOVA model can be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{TR}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[H-(\frac{1}{{{n}_{a}}\cdot {{n}_{b}}\cdot m})J]y \\ = & {{y}^{\prime }}[H-(\frac{1}{18})J]y \\ = & 9.7311 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ H\,\! }[/math] is the hat matrix and [math]\displaystyle{ J\,\! }[/math] is the matrix of ones. Since five effect terms ([math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math]) are used in the model, the number of degrees of freedom associated with [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{TR}}\,\! }[/math] is five ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{TR}})=5\,\! }[/math]).

The total sum of squares, [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{T}}\,\! }[/math], can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{T}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[I-(\frac{1}{{{n}_{a}}\cdot {{n}_{b}}\cdot m})J]y \\ = & {{y}^{\prime }}[I-(\frac{1}{18})J]y \\ = & 10.7178 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are 18 observed response values, the number of degrees of freedom associated with the total sum of squares is 17 ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{T}})=17\,\! }[/math]). The error sum of squares can now be obtained:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{E}}= & S{{S}_{T}}-S{{S}_{TR}} \\ = & 10.7178-9.7311 \\ = & 0.9867 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are three replicates of the full factorial experiment, all of the error sum of squares is pure error. (This can also be seen from the preceding figure, where each treatment combination of the full factorial design is repeated three times.) The number of degrees of freedom associated with the error sum of squares is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} dof(S{{S}_{E}})= & dof(S{{S}_{T}})-dof(S{{S}_{TR}}) \\ = & 17-5 \\ = & 12 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Calculation of Extra Sum of Squares for the Factors

The sequential sum of squares for factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{A}}= & S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}})-S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ) \\ = & {{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y-0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}={{X}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}{{(X_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}^{\prime }{{X}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}})}^{-1}}X_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}^{\prime }\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}\,\! }[/math] is the matrix containing only the first three columns of the [math]\displaystyle{ X\,\! }[/math] matrix. Thus:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{A}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y-0 \\ = & 4.5811-0 \\ = & 4.5811 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are two independent effects ([math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math]) for factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math], the degrees of freedom associated with [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{A}}\,\! }[/math] are two ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{A}})=2\,\! }[/math]).

Similarly, the sum of squares for factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{B}}= & S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}},{{\delta }_{1}})-S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}) \\ = & {{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}},{{\delta }_{1}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y-{{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y \\ = & 9.4900-4.5811 \\ = & 4.9089 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there is one independent effect, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], for factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math], the number of degrees of freedom associated with [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{B}}\,\! }[/math] is one ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{B}})=1\,\! }[/math]).

The sum of squares for the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{AB}}= & S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}},{{\delta }_{1}},{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}},{{(\tau \delta )}_{21}})-S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}},{{\delta }_{1}}) \\ = & S{{S}_{TR}}-S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}},{{\delta }_{1}}) \\ = & 9.7311-9.4900 \\ = & 0.2411 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are two independent interaction effects, [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math], the number of degrees of freedom associated with [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{AB}}\,\! }[/math] is two ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{AB}})=2\,\! }[/math]).

Calculation of the Test Statistics

Knowing the sum of squares, the test statistic for each of the factors can be calculated. Analyzing the interaction first, the test statistic for interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{({{f}_{0}})}_{AB}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{AB}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{0.2411/2}{0.9867/12} \\ = & 1.47 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value corresponding to this statistic, based on the [math]\displaystyle{ F\,\! }[/math] distribution with 2 degrees of freedom in the numerator and 12 degrees of freedom in the denominator, is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p\text{ }value= & 1-P(F\le {{({{f}_{0}})}_{AB}}) \\ = & 1-0.7307 \\ = & 0.2693 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

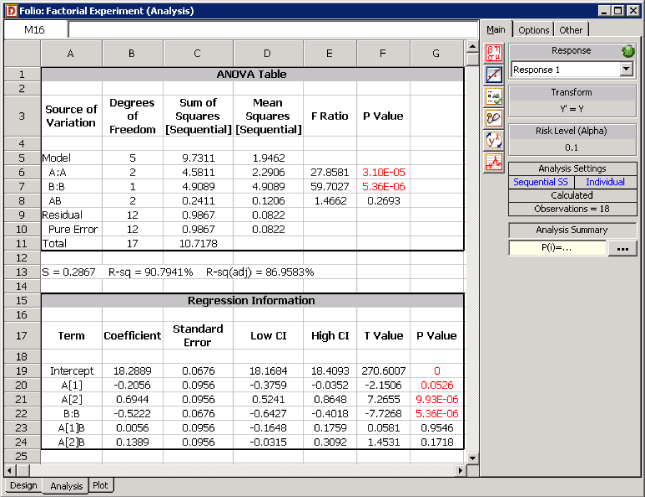

Assuming that the desired significance level is 0.1, since [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value > 0.1, we fail to reject [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{(\tau \delta )}_{ij}}=0\,\! }[/math] and conclude that the interaction between speed and fuel additive does not significantly affect the mileage of the sports utility vehicle. DOE++ displays this result in the ANOVA table, as shown in the following figure. In the absence of the interaction, the analysis of main effects becomes important.

The test statistic for factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{({{f}_{0}})}_{A}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{A}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{S{{S}_{A}}/dof(S{{S}_{A}})}{S{{S}_{E}}/dof(S{{S}_{E}})} \\ = & \frac{4.5811/2}{0.9867/12} \\ = & 27.86 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value corresponding to this statistic based on the [math]\displaystyle{ F\,\! }[/math] distribution with 2 degrees of freedom in the numerator and 12 degrees of freedom in the denominator is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p\text{ }value= & 1-P(F\le {{({{f}_{0}})}_{A}}) \\ = & 1-0.99997 \\ = & 0.00003 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value < 0.1, [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\tau }_{i}}=0\,\! }[/math] is rejected and it is concluded that factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] (or speed) has a significant effect on the mileage.

The test statistic for factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{({{f}_{0}})}_{B}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{B}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{4.9089/1}{0.9867/12} \\ = & 59.7 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value corresponding to this statistic based on the [math]\displaystyle{ F\,\! }[/math] distribution with 2 degrees of freedom in the numerator and 12 degrees of freedom in the denominator is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p\text{ }value= & 1-P(F\le {{({{f}_{0}})}_{B}}) \\ = & 1-0.999995 \\ = & 0.000005 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value < 0.1, [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\delta }_{j}}=0\,\! }[/math] is rejected and it is concluded that factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] (or fuel additive type) has a significant effect on the mileage.

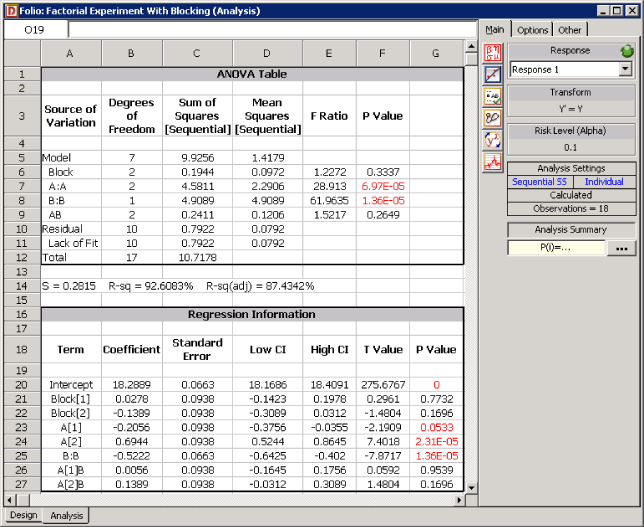

Therefore, it can be concluded that speed and fuel additive type affect the mileage of the vehicle significantly. The results are displayed in the ANOVA table of the following figure.

Calculation of Effect Coefficients

Results for the effect coefficients of the model of the regression version of the ANOVA model are displayed in the Regression Information table in the following figure. Calculations of the results in this table are discussed next. The effect coefficients can be calculated as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \hat{\beta }= & {{({{X}^{\prime }}X)}^{-1}}{{X}^{\prime }}y \\ = & \left[ \begin{matrix} 18.2889 \\ -0.2056 \\ 0.6944 \\ -0.5222 \\ 0.0056 \\ 0.1389 \\ \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mu }=18.2889\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\hat{\tau }}_{1}}=-0.2056\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\hat{\tau }}_{2}}=0.6944\,\! }[/math] etc. As mentioned previously, these coefficients are displayed as Intercept, A[1] and A[2] respectively depending on the name of the factor used in the experimental design. The standard error for each of these estimates is obtained using the diagonal elements of the variance-covariance matrix [math]\displaystyle{ C\,\! }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} C= & {{{\hat{\sigma }}}^{2}}{{({{X}^{\prime }}X)}^{-1}} \\ = & M{{S}_{E}}\cdot {{({{X}^{\prime }}X)}^{-1}} \\ = & \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.0046 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0.0091 & -0.0046 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -0.0046 & 0.0091 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.0046 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.0091 & -0.0046 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & -0.0046 & 0.0091 \\ \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

For example, the standard error for [math]\displaystyle{ {{\hat{\tau }}_{1}}\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} se({{{\hat{\tau }}}_{1}})= & \sqrt{{{C}_{22}}} \\ = & \sqrt{0.0091} \\ = & 0.0956 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Then the [math]\displaystyle{ t\,\! }[/math] statistic for [math]\displaystyle{ {{\hat{\tau }}_{1}}\,\! }[/math] can be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{t}_{0}}= & \frac{{{{\hat{\tau }}}_{1}}}{se({{{\hat{\tau }}}_{1}})} \\ = & \frac{-0.2056}{0.0956} \\ = & -2.1506 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value corresponding to this statistic is:

Confidence intervals on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] can also be calculated. The 90% limits on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} = & {{{\hat{\tau }}}_{1}}\pm {{t}_{\alpha /2,n-(k+1)}}\sqrt{{{C}_{22}}} \\ = & {{\tau }_{1}}\pm {{t}_{0.05,12}}\sqrt{{{C}_{22}}} \\ = & -0.2056\pm 0.1704 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Thus, the 90% limits on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] are [math]\displaystyle{ -0.3760\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ -0.0352\,\! }[/math] respectively. Results for other coefficients are obtained in a similar manner.

Least Squares Means

The estimated mean response corresponding to the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th level of any factor is obtained using the adjusted estimated mean which is also called the least squares mean. For example, the mean response corresponding to the first level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \mu +{{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math]. An estimate of this is [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mu }+{{\hat{\tau }}_{1}}\,\! }[/math] or ([math]\displaystyle{ 18.2889+(-0.2056)=18.0833\,\! }[/math]). Similarly, the estimated response at the third level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mu }+{{\hat{\tau }}_{3}}\,\! }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\mu }+(-{{\hat{\tau }}_{1}}-{{\hat{\tau }}_{2}})\,\! }[/math] or ([math]\displaystyle{ 18.2889+(0.2056-0.6944)=17.8001\,\! }[/math]).

Residual Analysis

As in the case of single factor experiments, plots of residuals can also be used to check for model adequacy in factorial experiments. Box-Cox transformations are also available in DOE++ for factorial experiments.

Factorial Experiments with a Single Replicate

If a factorial experiment is run only for a single replicate then it is not possible to test hypotheses about the main effects and interactions as the error sum of squares cannot be obtained. This is because the number of observations in a single replicate equals the number of terms in the ANOVA model. Hence the model fits the data perfectly and no degrees of freedom are available to obtain the error sum of squares. For example, if the two factor experiment to study the effect of speed and fuel additive type on mileage was run only as a single replicate there would be only six response values. The regression version of the ANOVA model has six terms and therefore will fit the six response values perfectly. The error sum of squares, [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{E}}\,\! }[/math], for this case will be equal to zero. In some single replicate factorial experiments it is possible to assume that the interaction effects are negligible. In this case, the interaction mean square can be used as error mean square, [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{E}}\,\! }[/math], to test hypotheses about the main effects. However, such assumptions are not applicable in all cases and should be used carefully.

Blocking

Many times a factorial experiment requires so many runs that not all of them can be completed under homogeneous conditions. This may lead to inclusion of the effects of nuisance factors into the investigation. Nuisance factors are factors that have an effect on the response but are not of primary interest to the investigator. For example, two replicates of a two factor factorial experiment require eight runs. If four runs require the duration of one day to be completed, then the total experiment will require two days to be completed. The difference in the conditions on the two days may introduce effects on the response that are not the result of the two factors being investigated. Therefore, the day is a nuisance factor for this experiment. Nuisance factors can be accounted for using blocking. In blocking, experimental runs are separated based on levels of the nuisance factor. For the case of the two factor factorial experiment (where the day is a nuisance factor), separation can be made into two groups or blocks: runs that are carried out on the first day belong to block 1, and runs that are carried out on the second day belong to block 2. Thus, within each block conditions are the same with respect to the nuisance factor. As a result, each block investigates the effects of the factors of interest, while the difference in the blocks measures the effect of the nuisance factor. For the example of the two factor factorial experiment, a possible assignment of runs to the blocks could be as follows: one replicate of the experiment is assigned to block 1 and the second replicate is assigned to block 2 (now each block contains all possible treatment combinations). Within each block, runs are subjected to randomization (i.e., randomization is now restricted to the runs within a block). Such a design, where each block contains one complete replicate and the treatments within a block are subjected to randomization, is called randomized complete block design.

In summary, blocking should always be used to account for the effects of nuisance factors if it is not possible to hold the nuisance factor at a constant level through all of the experimental runs. Randomization should be used within each block to counter the effects of any unknown variability that may still be present.

Example

Consider the experiment of the fifth table where the mileage of a sports utility vehicle was investigated for the effects of speed and fuel additive type. Now assume that the three replicates for this experiment were carried out on three different vehicles. To ensure that the variation from one vehicle to another does not have an effect on the analysis, each vehicle is considered as one block. See the experiment design in the following figure.

For the purpose of the analysis, the block is considered as a main effect except that it is assumed that interactions between the block and the other main effects do not exist. Therefore, there is one block main effect (having three levels - block 1, block 2 and block 3), two main effects (speed -having three levels; and fuel additive type - having two levels) and one interaction effect (speed-fuel additive interaction) for this experiment. Let [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] represent the block effects. The hypothesis test on the block main effect checks if there is a significant variation from one vehicle to the other. The statements for the hypothesis test are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & {{H}_{0}}: & {{\zeta }_{1}}={{\zeta }_{2}}={{\zeta }_{3}}=0\text{ (no main effect of block)} \\ & {{H}_{1}}: & {{\zeta }_{i}}\ne 0\text{ for at least one }i \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The test statistic for this test is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{F}_{0}}=\frac{M{{S}_{Block}}}{M{{S}_{E}}}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{Block}}\,\! }[/math] represents the mean square for the block main effect and [math]\displaystyle{ M{{S}_{E}}\,\! }[/math] is the error mean square. The hypothesis statements and test statistics to test the significance of factors [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] (speed), [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] (fuel additive) and the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] (speed-fuel additive interaction) can be obtained as explained in the example. The ANOVA model for this example can be written as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{Y}_{ijk}}=\mu +{{\zeta }_{i}}+{{\tau }_{j}}+{{\delta }_{k}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}+{{\epsilon }_{ijk}}\,\! }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu \,\! }[/math] represents the overall mean effect

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] is the effect of the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th level of the block ([math]\displaystyle{ i=1,2,3\,\! }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] is the effect of the [math]\displaystyle{ j\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ j=1,2,3\,\! }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{k}}\,\! }[/math] is the effect of the [math]\displaystyle{ k\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ k=1,2\,\! }[/math])

- [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}\,\! }[/math] represents the interaction effect between [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]

- and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\epsilon }_{ijk}}\,\! }[/math] represents the random error terms (which are assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero and variance of [math]\displaystyle{ {{\sigma }^{2}}\,\! }[/math])

In order to calculate the test statistics, it is convenient to express the ANOVA model of the equation given above in the form [math]\displaystyle{ y=X\beta +\epsilon \,\! }[/math]. This can be done as explained next.

Expression of the ANOVA Model as [math]\displaystyle{ y=X\beta +\epsilon \,\! }[/math]

Since the effects [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{i}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{j}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{k}}\,\! }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}\,\! }[/math] are defined as deviations from the overall mean, the following constraints exist.

Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \underset{i=1}{\overset{3}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\zeta }_{i}}= & 0 \\ & \text{or }{{\zeta }_{1}}+{{\zeta }_{2}}+{{\zeta }_{3}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, only two of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{i}}\,\! }[/math] effects are independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{2}}\,\! }[/math] are independent, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{3}}=-({{\zeta }_{1}}+{{\zeta }_{2}})\,\! }[/math]. (The null hypothesis to test the significance of the blocks can be rewritten using only the independent effects as [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\zeta }_{1}}={{\zeta }_{2}}=0\,\! }[/math].) In DOE++, the independent block effects, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], are displayed as Block[1] and Block[2], respectively.

Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \underset{j=1}{\overset{3}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\tau }_{j}}= & 0 \\ & \text{or }{{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}}+{{\tau }_{3}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, only two of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{j}}\,\! }[/math] effects are independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math] are independent, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{3}}=-({{\tau }_{1}}+{{\tau }_{2}})\,\! }[/math]. The independent effects, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], are displayed as A[1] and A[2], respectively.

Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{k}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \underset{k=1}{\overset{2}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{\delta }_{k}}= & 0 \\ & \text{or }{{\delta }_{1}}+{{\delta }_{2}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Therefore, only one of the [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{k}}\,\! }[/math] effects is independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math] is independent, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{2}}=-{{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math]. The independent effect, [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], is displayed as B:B.

Constraints on [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}\,\! }[/math] are:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \underset{j=1}{\overset{3}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}= & 0 \\ & \text{and }\underset{k=1}{\overset{2}{\mathop \sum }}\,{{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}= & 0 \\ & \text{or }{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{31}}= & 0 \\ & {{(\tau \delta )}_{12}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{22}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{32}}= & 0 \\ & \text{and }{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{12}}= & 0 \\ & {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{22}}= & 0 \\ & {{(\tau \delta )}_{31}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{32}}= & 0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The last five equations given above represent four constraints as only four of the five equations are independent. Therefore, only two out of the six [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{jk}}\,\! }[/math] effects are independent. Assuming that [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math] are independent, we can express the other four effects in terms of these effects. The independent effects, [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math], are displayed as A[1]B and A[2]B, respectively.

The regression version of the ANOVA model can be obtained using indicator variables. Since the block has three levels, two indicator variables, [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{1}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{2}}\,\! }[/math], are required, which need to be coded as shown next:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \text{Block 1}: & {{x}_{1}}=1,\text{ }{{x}_{2}}=0\text{ } \\ & \text{Block 2}: & {{x}_{1}}=0,\text{ }{{x}_{2}}=1\text{ } \\ & \text{Block 3}: & {{x}_{1}}=-1,\text{ }{{x}_{2}}=-1\text{ } \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] has three levels and two indicator variables, [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{3}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{4}}\,\! }[/math], are required:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \text{Treatment Effect }{{\tau }_{1}}: & {{x}_{3}}=1,\text{ }{{x}_{4}}=0 \\ & \text{Treatment Effect }{{\tau }_{2}}: & {{x}_{3}}=0,\text{ }{{x}_{4}}=1\text{ } \\ & \text{Treatment Effect }{{\tau }_{3}}: & {{x}_{3}}=-1,\text{ }{{x}_{4}}=-1\text{ } \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] has two levels and can be represented using one indicator variable, [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{5}}\,\! }[/math], as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \text{Treatment Effect }{{\delta }_{1}}: & {{x}_{5}}=1 \\ & \text{Treatment Effect }{{\delta }_{2}}: & {{x}_{5}}=-1 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] interaction will be represented by [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{3}}{{x}_{5}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{x}_{4}}{{x}_{5}}\,\! }[/math]. The regression version of the ANOVA model can finally be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ Y=\mu +{{\zeta }_{1}}\cdot {{x}_{1}}+{{\zeta }_{2}}\cdot {{x}_{2}}+{{\tau }_{1}}\cdot {{x}_{3}}+{{\tau }_{2}}\cdot {{x}_{4}}+{{\delta }_{1}}\cdot {{x}_{5}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\cdot {{x}_{3}}{{x}_{5}}+{{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\cdot {{x}_{4}}{{x}_{5}}+\epsilon \,\! }[/math]

In matrix notation this model can be expressed as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ y=X\beta +\epsilon \,\! }[/math]

- or:

Knowing [math]\displaystyle{ y\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ X\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \,\! }[/math], the sum of squares for the ANOVA model and the extra sum of squares for each of the factors can be calculated. These are used to calculate the mean squares that are used to obtain the test statistics.

Calculation of the Sum of Squares for the Model

The model sum of squares, [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{TR}}\,\! }[/math], for the ANOVA model of this example can be obtained as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & S{{S}_{TR}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[H-(\frac{1}{{{n}_{a}}\cdot {{n}_{b}}\cdot m})J]y \\ & = & {{y}^{\prime }}[H-(\frac{1}{18})J]y \\ & = & 9.9256 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since seven effect terms ([math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\tau }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{\delta }_{1}}\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{11}}\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{(\tau \delta )}_{21}}\,\! }[/math]) are used in the model the number of degrees of freedom associated with [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{TR}}\,\! }[/math] is seven ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{TR}})=7\,\! }[/math]).

The total sum of squares can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & S{{S}_{T}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[I-(\frac{1}{{{n}_{a}}\cdot {{n}_{b}}\cdot m})J]y \\ & = & {{y}^{\prime }}[H-(\frac{1}{18})J]y \\ & = & 10.7178 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are 18 observed response values, the number of degrees of freedom associated with the total sum of squares is 17 ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{T}})=17\,\! }[/math]). The error sum of squares can now be obtained:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{E}}= & S{{S}_{T}}-S{{S}_{TR}} \\ = & 10.7178-9.9256 \\ = & 0.7922 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The number of degrees of freedom associated with the error sum of squares is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} dof(S{{S}_{E}})= & dof(S{{S}_{T}})-dof(S{{S}_{TR}}) \\ = & 17-7 \\ = & 10 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are no true replicates of the treatments (as can be seen from the design of the previous figure, where all of the treatments are seen to be run just once), all of the error sum of squares is the sum of squares due to lack of fit. The lack of fit arises because the model used is not a full model since it is assumed that there are no interactions between blocks and other effects.

Calculation of the Extra Sum of Squares for the Factors

The sequential sum of squares for the blocks can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{Block}}= & S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}})-S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ) \\ = & {{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y-0 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ J\,\! }[/math] is the matrix of ones, [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}\,\! }[/math] is the hat matrix, which is calculated using [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}={{X}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}{{(X_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}^{\prime }{{X}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}})}^{-1}}X_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}^{\prime }\,\! }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}\,\! }[/math] is the matrix containing only the first three columns of the [math]\displaystyle{ X\,\! }[/math] matrix. Thus

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{Block}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y-0 \\ = & 0.1944-0 \\ = & 0.1944 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Since there are two independent block effects, and [math]\displaystyle{ {{\zeta }_{2}}\,\! }[/math], the number of degrees of freedom associated with [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{Blocks}}\,\! }[/math] is two ([math]\displaystyle{ dof(S{{S}_{Blocks}})=2\,\! }[/math]).

Similarly, the sequential sum of squares for factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S{{S}_{A}}= & S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}},{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}})-S{{S}_{TR}}(\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}) \\ = & {{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}},{{\tau }_{1}},{{\tau }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y-{{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\mu ,{{\zeta }_{1}},{{\zeta }_{2}}}}-(\frac{1}{18})J]y \\ = & 4.7756-0.1944 \\ = & 4.5812 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Sequential sum of squares for the other effects are obtained as [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{B}}=4.9089\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{AB}}=0.2411\,\! }[/math].

Calculation of the Test Statistics

Knowing the sum of squares, the test statistics for each of the factors can be calculated. For example, the test statistic for the main effect of the blocks is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {{({{f}_{0}})}_{Block}}= & \frac{M{{S}_{Block}}}{M{{S}_{E}}} \\ = & \frac{S{{S}_{Block}}/dof(S{{S}_{Blocks}})}{S{{S}_{E}}/dof(S{{S}_{E}})} \\ = & \frac{0.1944/2}{0.7922/10} \\ = & 1.227 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

The [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value corresponding to this statistic based on the [math]\displaystyle{ F\,\! }[/math] distribution with 2 degrees of freedom in the numerator and 10 degrees of freedom in the denominator is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} p\text{ }value= & 1-P(F\le {{({{f}_{0}})}_{Block}}) \\ = & 1-0.6663 \\ = & 0.3337 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

Assuming that the desired significance level is 0.1, since [math]\displaystyle{ p\,\! }[/math] value > 0.1, we fail to reject [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{0}}:{{\zeta }_{i}}=0\,\! }[/math] and conclude that there is no significant variation in the mileage from one vehicle to the other. Statistics to test the significance of other factors can be calculated in a similar manner. The complete analysis results obtained from DOE++ for this experiment are presented in the following figure.

Use of Regression to Calculate Sum of Squares

This section explains the reason behind the use of regression in DOE++ in all calculations related to the sum of squares. A number of textbooks present the method of direct summation to calculate the sum of squares. But this method is only applicable for balanced designs and may give incorrect results for unbalanced designs. For example, the sum of squares for factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] in a balanced factorial experiment with two factors, [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math], is given as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & S{{S}_{A}}= & \underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,{{n}_{b}}n{{({{{\bar{y}}}_{i..}}-{{{\bar{y}}}_{...}})}^{2}} \\ & = & \underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{i..}^{2}}{{{n}_{b}}n}-\frac{y_{...}^{2}}{{{n}_{a}}{{n}_{b}}n} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ {{n}_{a}}\,\! }[/math] represents the levels of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{n}_{b}}\,\! }[/math] represents the levels of factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ n\,\! }[/math] represents the number of samples for each combination of [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math]. The term [math]\displaystyle{ {{\bar{y}}_{i..}}\,\! }[/math] is the mean value for the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {{y}_{i..}}\,\! }[/math] is the sum of all observations at the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{y}_{...}}\,\! }[/math] is the sum of all observations.

The analogous term to calculate [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{A}}\,\! }[/math] in the case of an unbalanced design is given as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{A}}=\underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{i..}^{2}}{{{n}_{i.}}}-\frac{y_{...}^{2}}{{{n}_{..}}}\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ {{n}_{i.}}\,\! }[/math] is the number of observations at the [math]\displaystyle{ i\,\! }[/math]th level of factor [math]\displaystyle{ A\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {{n}_{..}}\,\! }[/math] is the total number of observations. Similarly, to calculate the sum of squares for factor [math]\displaystyle{ B\,\! }[/math] and interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math], the formulas are given as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & S{{S}_{B}}= & \underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{.j.}^{2}}{{{n}_{.j}}}-\frac{y_{...}^{2}}{{{n}_{..}}} \\ & S{{S}_{AB}}= & \underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{ij.}^{2}}{{{n}_{ij}}}-\underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{i..}^{2}}{{{n}_{i.}}}-\underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{.j.}^{2}}{{{n}_{.j}}}+\frac{y_{...}^{2}}{{{n}_{..}}} \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

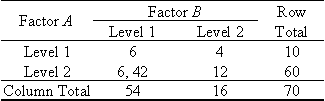

Applying these relations to the unbalanced data of the last table, the sum of squares for the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & S{{S}_{AB}}= & \underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{ij.}^{2}}{{{n}_{ij}}}-\underset{i=1}{\overset{{{n}_{a}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{i..}^{2}}{{{n}_{i.}}}-\underset{j=1}{\overset{{{n}_{b}}}{\mathop{\sum }}}\,\frac{y_{.j.}^{2}}{{{n}_{.j}}}+\frac{y_{...}^{2}}{{{n}_{..}}} \\ & = & \left( {{6}^{2}}+{{4}^{2}}+\frac{{{(42+6)}^{2}}}{2}+{{12}^{2}} \right)-\left( \frac{{{10}^{2}}}{2}+\frac{{{60}^{2}}}{3} \right) \\ & & -\left( \frac{{{54}^{2}}}{3}+\frac{{{16}^{2}}}{2} \right)+\frac{{{70}^{2}}}{5} \\ & = & -22 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

which is obviously incorrect since the sum of squares cannot be negative. For a detailed discussion on this refer to [23].

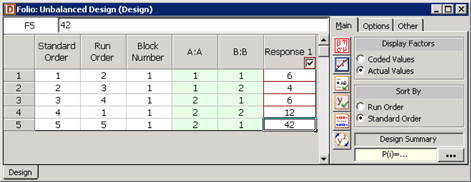

The correct sum of squares can be calculated as shown next. The [math]\displaystyle{ y\,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X\,\! }[/math] matrices for the design of the last table can be written as:

Then the sum of squares for the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] can be calculated as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S{{S}_{AB}}={{y}^{\prime }}[H-(1/5)J]y-{{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\tilde{\ }AB}}-(1/5)J]y\,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ H\,\! }[/math] is the hat matrix and [math]\displaystyle{ J\,\! }[/math] is the matrix of ones. The matrix [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{\tilde{\ }AB}}\,\! }[/math] can be calculated using [math]\displaystyle{ {{H}_{\tilde{\ }AB}}={{X}_{\tilde{\ }AB}}{{(X_{\tilde{\ }AB}^{\prime }{{X}_{\tilde{\ }AB}})}^{-1}}X_{\tilde{\ }AB}^{\prime }\,\! }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ {{X}_{\tilde{\ }AB}}\,\! }[/math] is the design matrix, [math]\displaystyle{ X\,\! }[/math], excluding the last column that represents the interaction effect [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math]. Thus, the sum of squares for the interaction [math]\displaystyle{ AB\,\! }[/math] is:

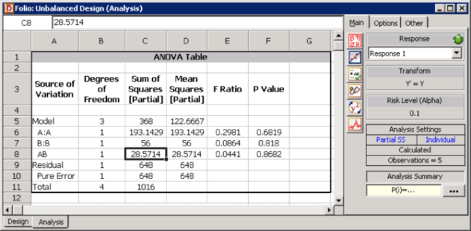

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & S{{S}_{AB}}= & {{y}^{\prime }}[H-(1/5)J]y-{{y}^{\prime }}[{{H}_{\tilde{\ }AB}}-(1/5)J]y \\ & = & 368-339.4286 \\ & = & 28.5714 \end{align}\,\! }[/math]

This is the value that is calculated by DOE++ (see the first figure below, for the experiment design and the second figure below for the analysis).